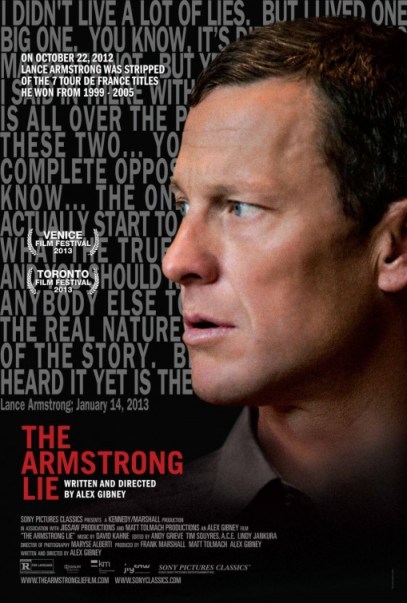

The Armstrong Lie (Alex Gibney, 2013)

The truth will out, and when it does, the bigger the lie that preceded it, the harder the fall of the liar. On such a simple premise has a filmmaking career been made.

Alex Gibney likes to tell stories about hubris and the overreach of power. In films like Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, Taxi to the Dark Side, Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer and We Steal Secrets: The Story of Wikileaks (released earlier this year), he crafts profiles of dominant personalities hoisted by their own petards (in Spitzer’s case, quite literally). We watch, fascinated, as men (they’re always men) who think they’re smarter than everyone else – and who really should know better – do very stupid (or illegal, or both) things. In The Armstrong Lie, Gibney tackles yet another big fish: Lance Armstrong, once hailed as the seven-time winner of the Tour de France and a renowned cancer survivor and activist, now brought low by a doping scandal.

What makes this particular film different from other works in the Gibney canon is that Gibney puts himself in the middle of the story. Originally setting out, in 2009, to make a film about Lance Armstrong’s comeback – and attempt to put the ever-present rumors of doping to rest – Gibney was forced to recalibrate his approach as investigators and rivals finally exposed Armstrong’s secrets. In his voiceover narration – and occasional off-camera questioning of Armstrong – Gibney reveals that he was as much a fool as the rest of the world in believing Armstrong’s deception. Still, knowing Gibney’s work as I do, I have to question how much he actually trusted Armstrong to begin with, and how much he may have been hoping for scandal. It certainly makes a better movie that way. No matter, for with his usual insightful and meticulous approach to his subject, Gibney creates yet another indelible portrait of a fallen idol. Who cares what his original intentions may or may not have been . . .

The movie begins in January of this year, as Armstrong speaks directly to the camera (and Gibney) just three hours after his revelatory interview with Oprah Winfrey. He is reflective, introspective and (mostly) humble: a changed man. Or is he? Much like Eliot Spitzer, he admits to past wrongdoing, but – even more than Spitzer – retains a hint of defiance and a certain lack of awareness of how much his deception has hurt his credibility and future prospects. Still, he is prepared to finally take his (legal) medicine, and it is to our benefit that he allows Gibney such intimate and repeated access to his evolving thoughts on his life and career.

Born in 1971, Lance Armstrong was a rising cycling star when, in 1996, he was diagnosed with testicular cancer. After undergoing aggressive treatment – some of which we see – Armstrong was pronounced free of the disease, and resumed his cycling career. He joined the United States Postal Service team in 1998, and in 1999 won the first of his 7 Tour de France titles. Always suspected of doping – which, the film shows, was (and maybe still is) something that quite a lot of cyclists were doing – Armstrong managed to beat back rumors and outfox investigators through cleverness, ruthless intimidation, and the employment of one very smart Italian doctor, Michele Ferrari. Indeed, it is fascinating to learn how the science of doping – using steroids, other harder-to-detect drugs, or transfusions of one’s own blood – evolved over the years. I had no idea the extent to which these athletes would go to gain an edge.

All of which is too bad, because one thing that is clear is that, doping or not, cycling is hard work, particularly in the Tour de France. The drugs may help more oxygen get into your bloodstream, but you – and you alone – still have to put in the grueling work to climb the mountain. These guys may have cheated, but they are still remarkable athletes. And, the film legitimately asks – without exonerating the cheaters – who was actually clean? Certainly not the organizers of the sport, many of whom seemed to know exactly what was going on.

The film also explores Armstrong’s rising celebrity, and how it allowed him to do great things, such as found Livestrong, and . . . less great things, such as accuse former friend and teammate Frankie Andreu – who had admitted to his own doping – and his wife Betsy of lying in court testimony, damaging Frankie’s career prospects. In Betsy Andreu, however, Armstrong may have met his match, for she is not ready to forgive him his threats and betrayal, as the film and recent editorials she has written make clear. Beware of bullying the wrong person . . .

It’s a complicated film about a complex individual undone by his belief in his own inviolable power and fame. Hubris is fascinating, especially when, in hindsight, you can see where the overreaching took place. For Armstrong, there were two significant missteps (other than doping in the first place):

- The first was his return to the cycling circuit in 2009. Had Armstrong been content to live out his life as a former champion, and to just accept that there would always be rumors associated with his victories, he would most likely have been able to keep his reputation, his tour titles, and his money. Instead . . .

- The second was his agreeing to be the subject of an Alex Gibney film. Come on, man! Had you never seen one of his movies before? It was only a matter of time before you, yourself, became a classic Gibney protagonist. Truly, it was karma.

Once again, Alex Gibney has created a parable for our time, which I highly recommend.

4 Comments